-40%

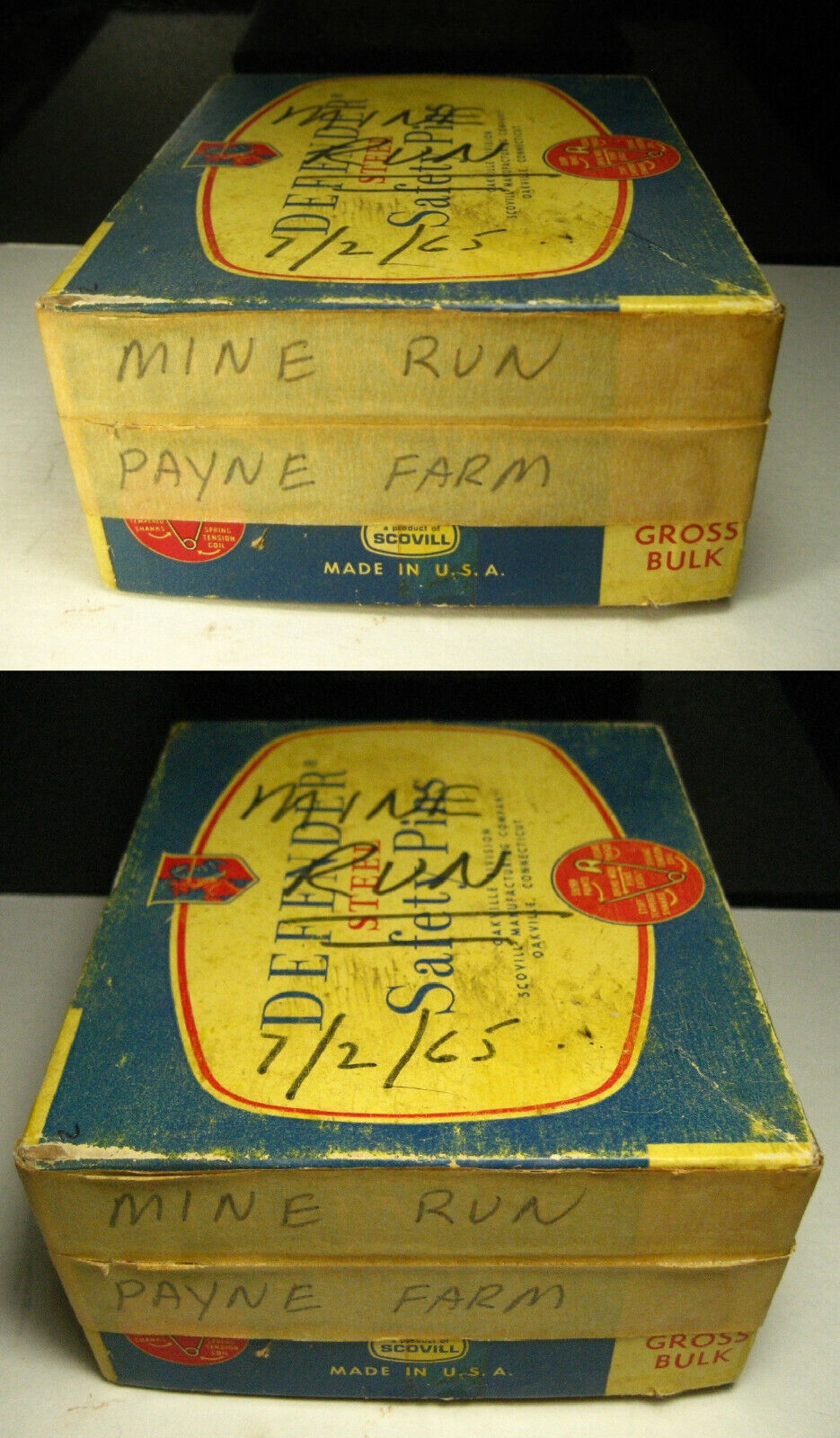

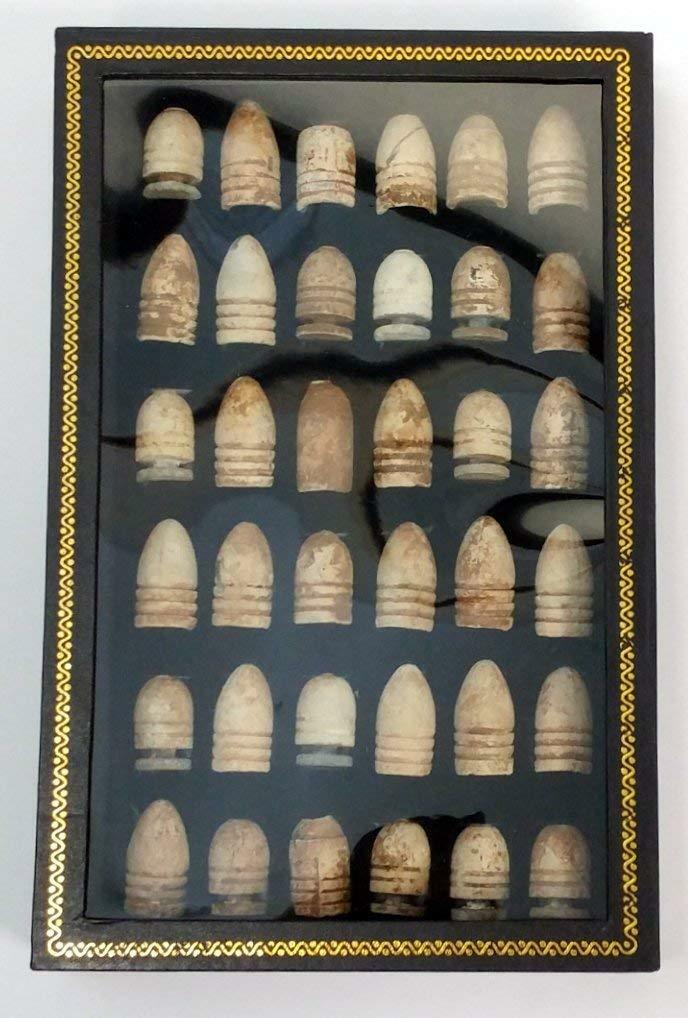

Mine Run VA Civil War Relic Found On The Payne Farm in 1965 Dropped .577 Bullet

$ 13.19

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

We are working as partners in conjunction with Gettysburg Relics to offer some very nice American Civil War relics for sale. The owner of Gettysburg Relics was the proprietor of Artifact at 777 on Cemetery Hill in Gettysburg for a number of years, and we are now selling exclusively on eBay.THE MINE RUN CAMPAIGN, VIRGINIA - DUG ON THE PAYNE FARM - Found July 2, 1965 - (Maps show the area of recovery) - From The Earl Gooding Collection - Dug on the Payne Farm at the site of the Mine Run campaign in Virginia

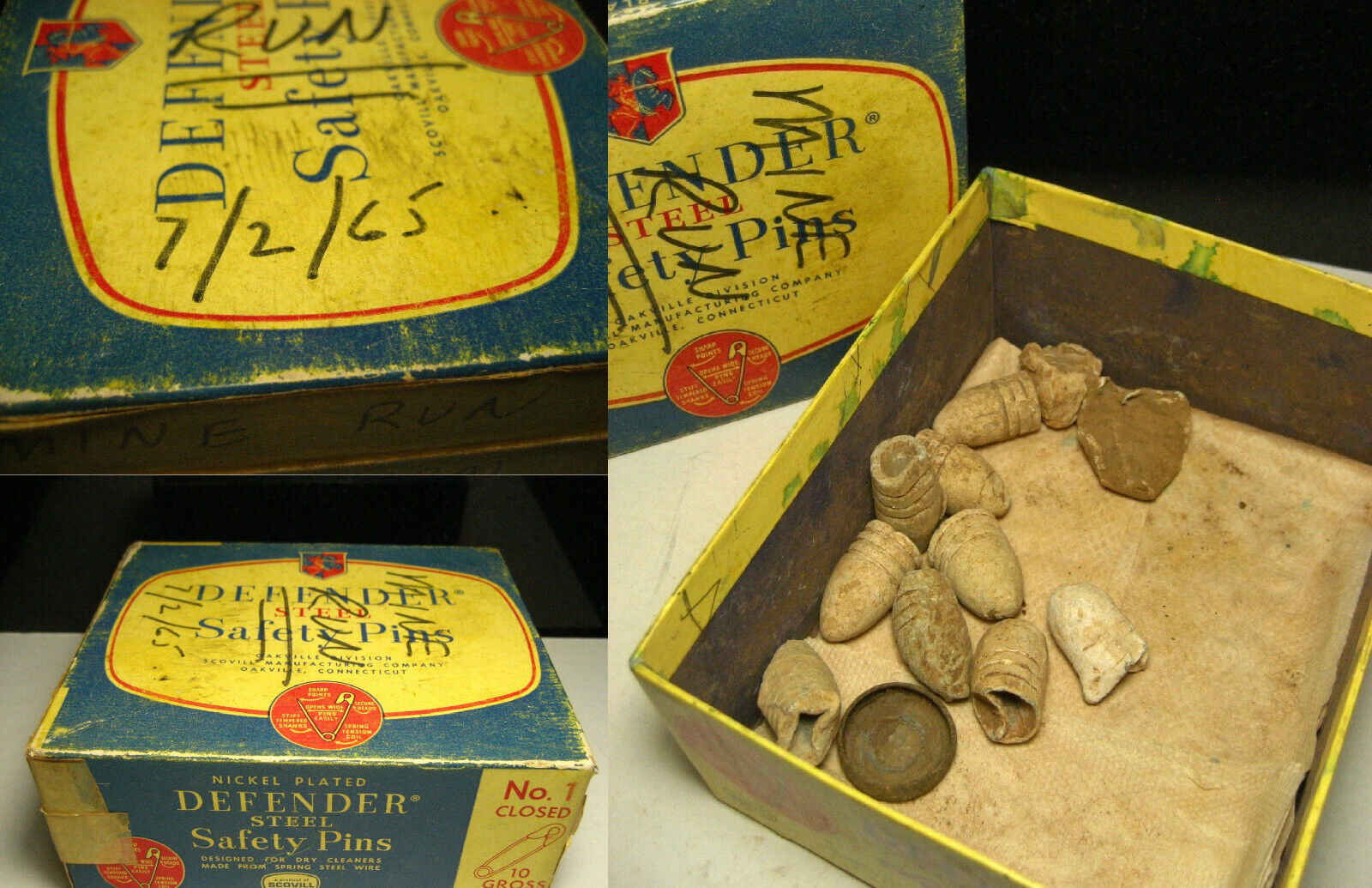

- A very nice Civil War relic dropped .577 caliber 3-ring rifle bullet

This very nice Civil War relic dropped .577 caliber 3-ring rifle bullet,

was recovered on the Payne Farm.

This artifact comes from the collection of a southern Maryland relic hunter who kept his finds from each expedition in small boxes marked with the location and often, the date. In most cases, it appeared as if he never opened the boxes again once they were stored away (they were still filled with dirt etc.) The box (not included) states that this grouping of artifacts were recovered at 'Mine Run - Payne Farm - 7/2/65'

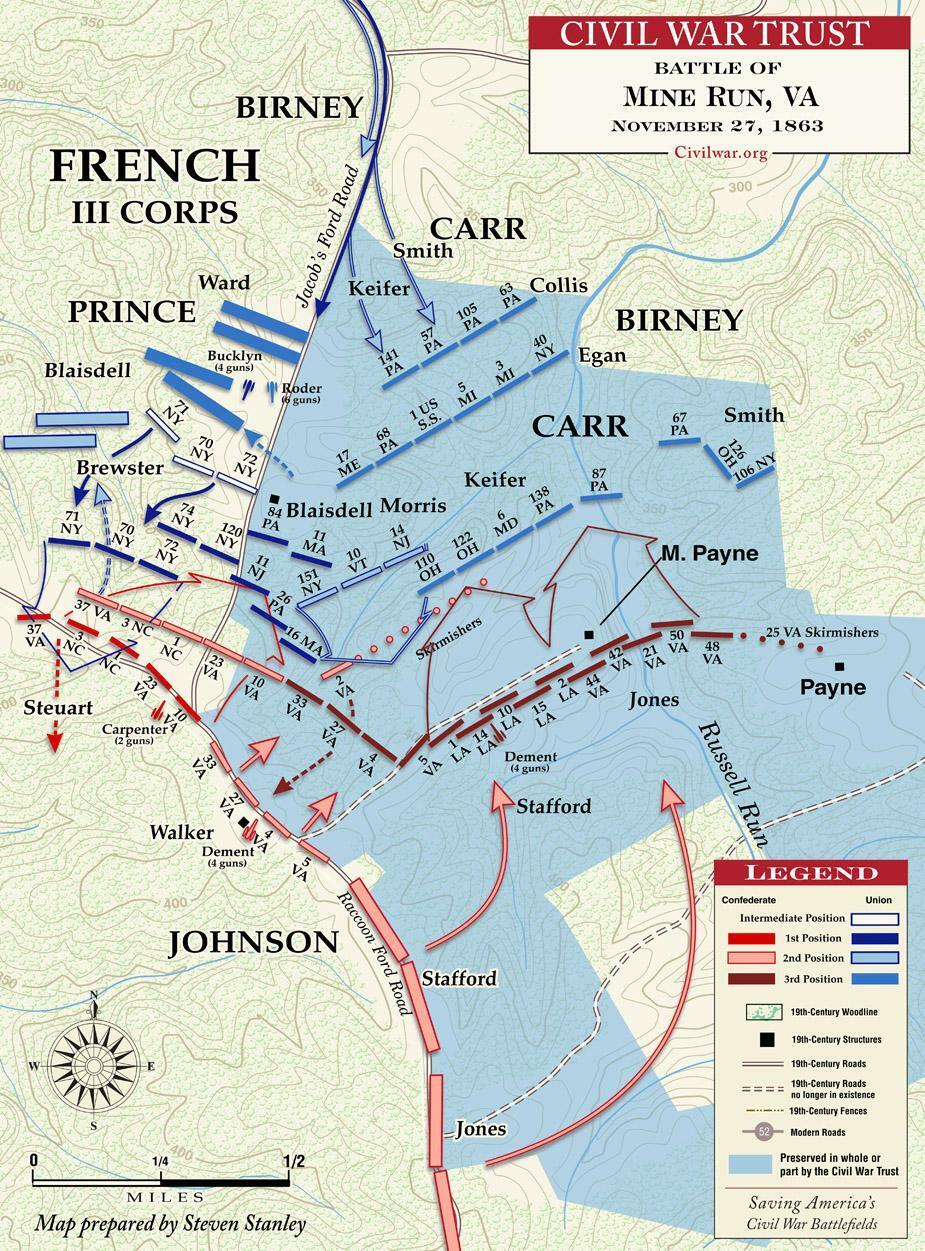

The Mine Run Campaign was a potential major battle that never came to be. After Gettysburg, Meade was pushed to advance against the Confederate Army in Virginia and did so in November of 1863. After an intense fight around Payne's Farm, the Union Army came upon Lee's Army which was well-entrenched along Mine Run. Attacks were considered and the position was probed but ultimately it was determined that the position was too strong.

'November 27 - December 2, 1863

Payne’s Farm and New Hope Church were the first and heaviest clashes of the Mine Run Campaign. In late November 1863, Meade attempted to steal a march through the Wilderness and strike the right flank of the Confederate army south of the Rapidan River. Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early in command of Ewell's Corps marched east on the Orange Turnpike to meet the advance of William French’s III Corps near Payne’s Farm. Carr’s division (US) attacked twice. Johnson’s division (CS) counterattacked but was scattered by heavy fire and broken terrain. After dark, Lee withdrew to prepared field fortifications along Mine Run. The next day the Union army closed on the Confederate position. Skirmishing was heavy, but a major attack did not materialize. Meade concluded that the Confederate line was too strong to attack and retired during the night of December 1-2, ending the winter campaign.

The engagement, unexpected by both sides, pitted the Federal III Corps, led by Maj. Gen. William “Blinky” French, against most of the Confederate division commanded by Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson. Federals surprised the Confederates, who doubled back and threw themselves into the fight with ferocity. “The Federals were as thick as black birds in front of us,” one North Carolinian said.

The engagement marked the first significant contact between the armies in what became known as the Mine Run campaign.

the engagement made quite an impression on the men who fought here. “It was truly a baptism of fire, while it was a deluge of lead and iron that swept over us, “ wrote a member of the 10th Vermont. A member of the 3rd North Carolina, meanwhile, said it was “as warm a contest as this regiment was ever engaged in. . . . It seemed as if the enemy was throwing minie-balls upon us by the bucket-full, when the battle got fairly under way.”

After their initial success, French’s men bogged down. Johnson’s swelling numbers forced the Federals to redeploy to prevent themselves from being outflanked. The ground dipped and rose in steep ravines, making it even more difficult for the men to secure their position.

Payne's Farm Final Assault Field

The final Confederate assaults launched across this field with little coordination, resulting, said one Louisianan, “in nothing but the loss of a considerable number of lives.”

The final confrontation unfolded across an open field, with Confederates launching piecemeal attacks that Federals successfully beat back. “It was a desperate effort to dislodge us,” a Federal Marylander said.

Old Allegheny reported the results differently: “The brave officers and men of this division, attacked by a greatly superior force from an admirable position, turned upon him and drove him from the field, which he left strewn with arms, artillery, and infantry ammunition, his dead and dying.” At dark, though, it was his men who withdrew from the field.

Johnson’s aggressiveness foiled the overall Federal maneuver, though—something that would have important ramifications in the days ahead as the campaign unfolded.

November 27 marks the anniversary of the 1863 battle of Payne’s Farm, part of the Mine Run campaign. Elements of the Army of the Potomac and Army of Northern Virginia, converging toward a wayside in the Virginia Wilderness known as Robinson’s Tavern along the Orange Plank Road, stumbled into each other. The ensuing fight, known as the battle of Payne’s Farm, was “was one of the sharpest engagements of the war, and was strongly contested by both sides,” said Edwin L. Wage of the 151st New York.

Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s single division threw itself into the Union Third and Sixth Corps, bottlenecked along the Jacob’s Ford Road. Federals enjoyed a 3-to-1 advantage on the battlefield—6-to-1 factoring in the stymied Sixth Corps—but the Federals nonetheless came off worse for the wear, with 943 casualties compared to 545 Confederates killed, wounded, and missing. Fighting “ceased only when it became too dark to see,” Wage wrote. “Neither could claim a victory.”

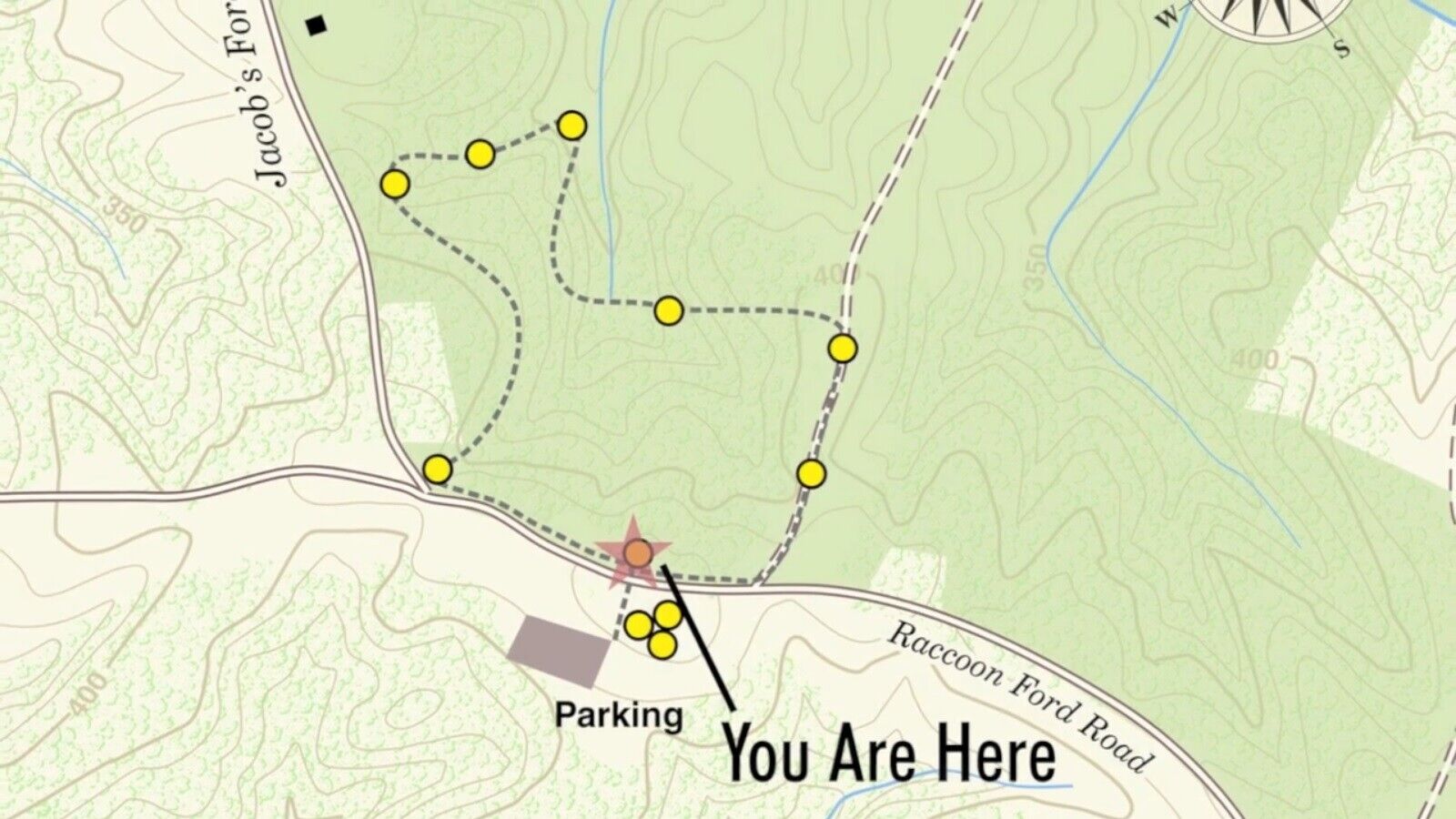

The scene of the heaviest casualties during the Union army's 1863 Mine Run campaign, the 685-acre battlefield is one of the most pristine on the East Coast--and least-known.

Now, after years of work by the Civil War Trust, Piedmont Environmental Council and local volunteers, it is beginning to welcome visitors. And thanks to its inclusion in the popular multi-state Civil War Trails program, the site will soon be known to thousands of people across the mid-Atlantic and nation.

A 1.5-mile self-guided walking trail through the site's woods and fields has been built, with the battle's history interpreted by a series of wayside markers that a Civil War Trails crew finished installing last week.

Union Gen. George Gordon Meade, urged on by President Abraham Lincoln, launched the Mine Run campaign in late November 1863 to dislodge and outflank Gen. Robert E. Lee's army, aiming to get between it and Richmond.

The Battle of Payne's Farm, fought between the Rapidan River and the crossroads at Robinson's Tavern (also known as Robertson's Tavern) in Locust Grove, occurred on Nov. 27 as the two armies, unaware, blundered into each other--much like the initial action at Gettysburg four months earlier.

Meade later broke off the campaign when Lee's forces entrenched behind Mine Run, creating what he judged were impregnable defenses, and the winter weather turned bitter cold. But he and his troops soon returned to the area, waging the full-blown Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, according to Garry Adelman, director of history and education at the Civil War Trust.

"Since the Union army failed in its objective to outflank and damage the Confederates, Meade learned critical information about advancing an army through that part of the Virginia 'Wilderness'--something that would come in very handy the following spring when the Union advanced again," he said in an interview.

Adelman led the team of historians who painstakingly researched the Payne's Farm battle and designed the walking trail. Their work revealed the fact that, contrary to long-held belief, the heaviest fighting happened in woods north of Zoar Road, not in the open fields to their south.

The landscape, including the historic roads nearby, is remarkably unchanged since that day in 1863, Adelman said.

"The remote location of the battlefield and its long history of agricultural use make this one of the best-preserved Civil War sites in America," a newly erected interpretive sign at Zoar Baptist Church on Raccoon Ford Road tells visitors.'

A provenance letter will be included.

We include as much documentation with the relics as we possess. This includes copies of tags

if there are original identification tags or maps, as well as a signed letter of provenance with the specific recovery information.

All of the collections that we are offering for sale are guaranteed to be authentic, and are either older recoveries, found before the 1960s when it was still legal to metal detect battlefields, or were recovered on private property with permission. Some land on Battlefields that is now Federally owned, or owned by the Trust, was acquired after the items were recovered. We will not sell any items that were recovered illegally, nor will we sell any items that we suspect were recovered illegally.

Thank you for viewing!