-40%

Siege of Port Hudson Louisiana LA Civil War Battle Relic Fired 577 Rifle Bullet

$ 13.19

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

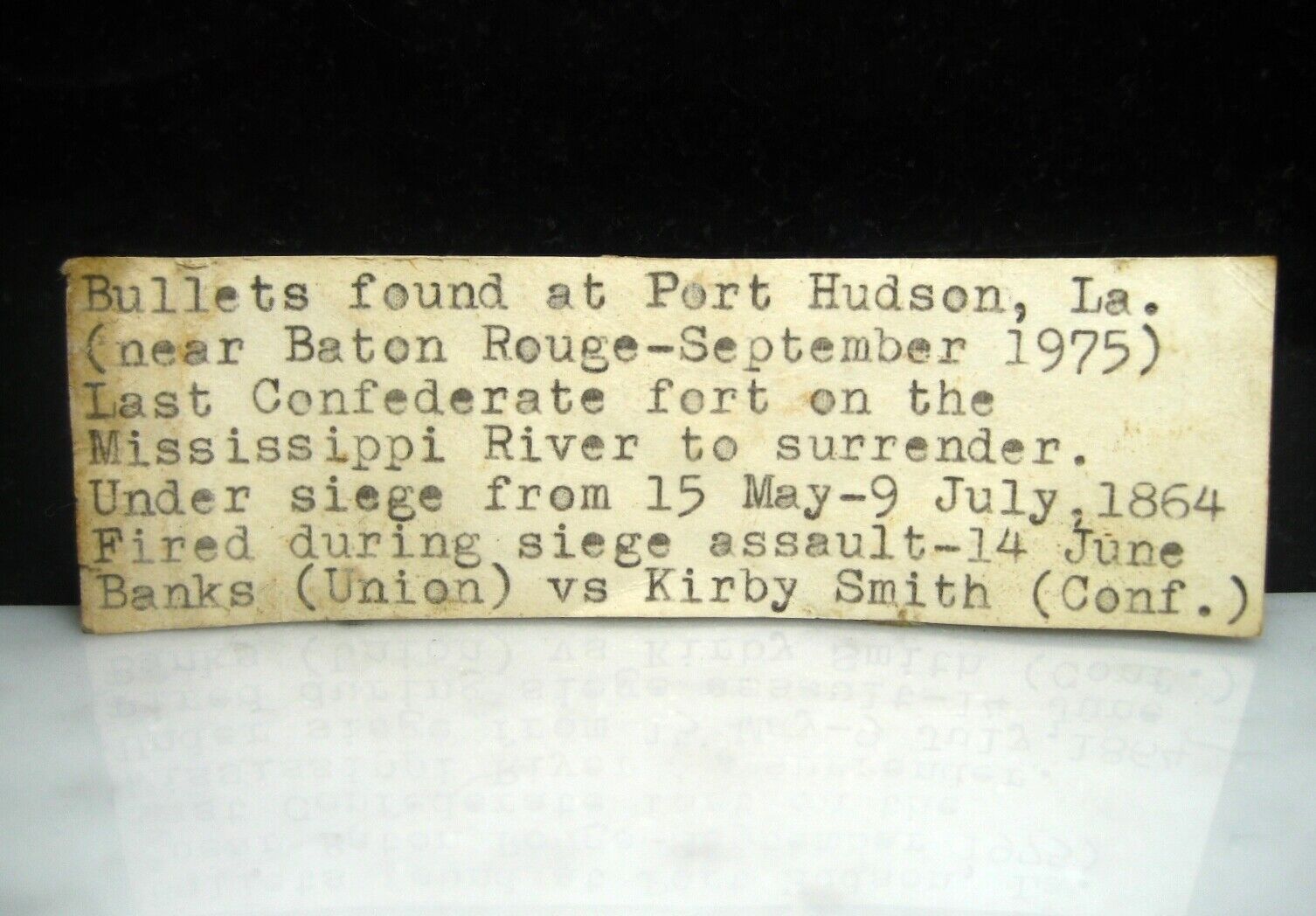

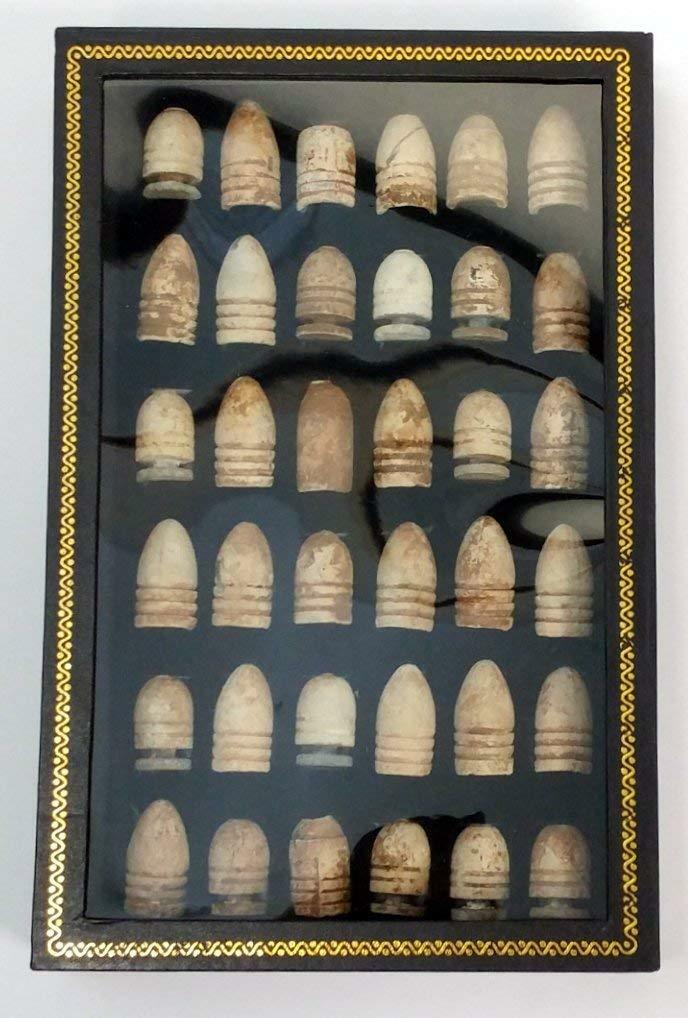

We are working as partners in conjunction with Gettysburg Relics to offer some very nice American Civil War relics for sale.The owner of Gettysburg Relics was the proprietor of Artifact at 777 on Cemetery Hill in Gettysburg for a number of years, and we are now selling exclusively on eBay.THE SIEGE OF PORT HUDSON, LOUISIANA, RECOVERED IN THE AREA OF THE ASSAULT ON THE CONFEDERATE FORT AT THIS PLACE - FOUND IN SEPTEMBER 1975 - FROM THE COLLECTION OF WILLIAM A. REGER, OF BERKS COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA - Here is a very nice Civil War relic Fired high impact .577 3-Ring Rifle Bullet

This very nice

Fired high impact .577 caliber 3-Ring Rifle Bullet,

was recovered at the site of the Siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana - in September 1975. This bullet comes from the large collection of William A. Reger, a relic hunter from Berks County, Pennsylvania who was active from the late 1950s to the mid 1970s. Reger kept his own original type-writer typed tags with the relic groupings. In this case, the tag is not included, as it was the only one in this grouping, however, a copy of the tag, as well as a provenance letter, will be included. Reger passed away in Reading, Pennsylvania in 2011.

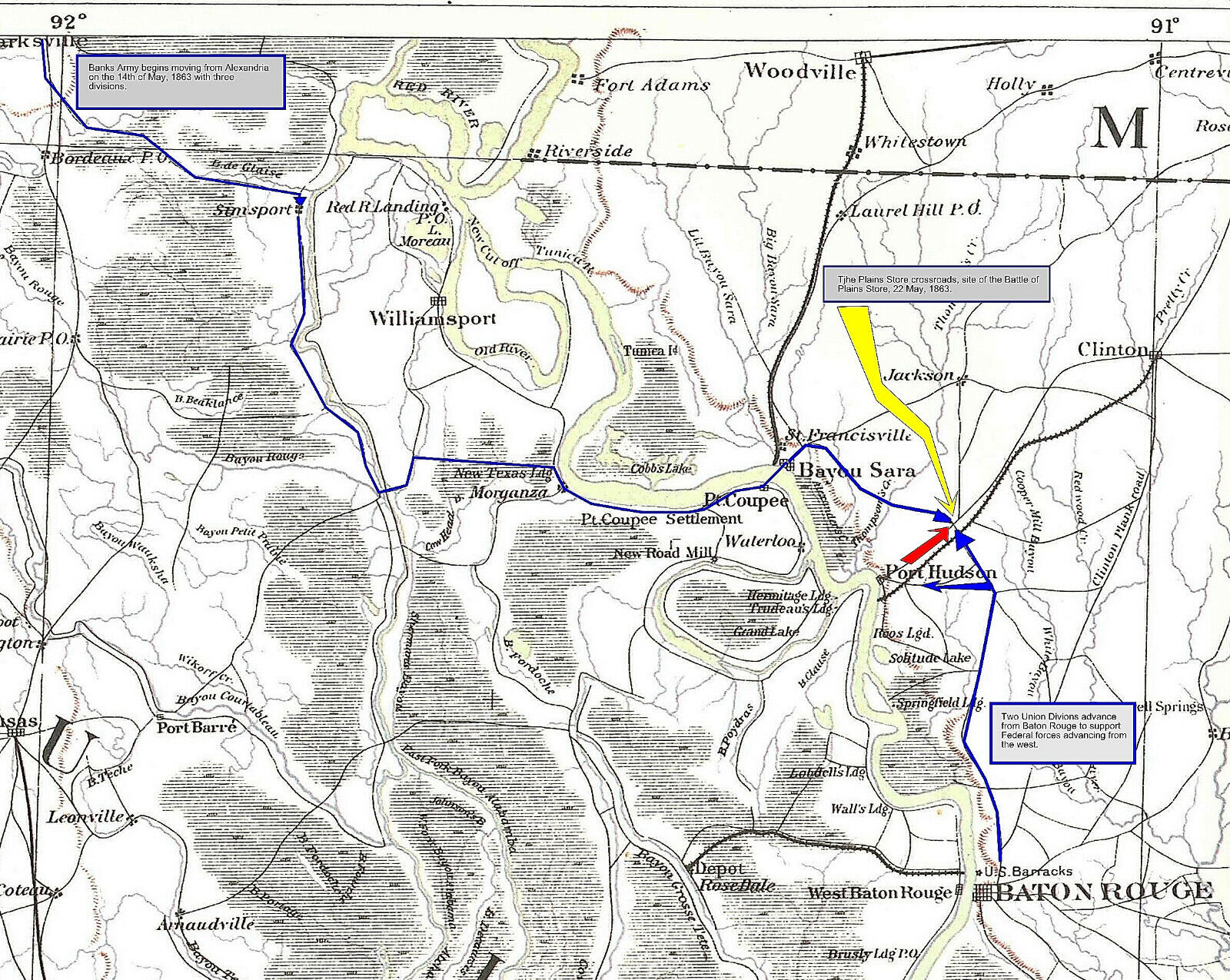

'The Siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana, (May 22 – July 9, 1863) was the final engagement in the Union campaign to recapture the Mississippi River in the American Civil War.

While Union General Ulysses Grant was besieging Vicksburg upriver, General Nathaniel Banks was ordered to capture the lower Mississippi Confederate stronghold of Port Hudson, in order to go to Grant's aid. When his assault failed, Banks settled into a 48-day siege, the longest in US military history up to that point. A second attack also failed, and it was only after the fall of Vicksburg that the Confederate commander, General Franklin Gardner surrendered the port. The Union gained control of the river and navigation from the Gulf of Mexico through the Deep South and to the river's upper reaches.

The fighting and siege

The first infantry assault

Sieges and the assault of fortified positions are probably the most complex and demanding of military operations. The foremost authority on these matters at the time of the civil war was still the seventeenth century French engineer, the Marquis de Vauban, who designed many European fortification systems, and organized many successful sieges. The Confederate earthworks of Port Hudson, and their use of artillery lunettes show his influence.

General Gardner reinforced the picket lines shielding the Confederate grain mill and support shops of the areas near Little Sandy Creek, previously left unfortified because he had not considered a siege probable. Other Confederate troops remained outside the fortifications, consisting of 1200 troops under the command of Colonel John L. Logan. These represented all of Gardner's cavalry, the 9th Louisiana Battalion, Partisan Rangers, and two artillery pieces of Robert's battery. These troops slowed the encirclement of Banks troops, and prevented them from discovering the weaknesses in the defenses. Due to these delays, the infantry assault was scheduled for May 27, 1863, five days after the encirclement and time enough for Gardner to complete the ring of defenses around Port Hudson. He also had sufficient time to move artillery from the river side of the fort to the east side fronting the Federal forces.

Weitzel's morning attacks

Banks had set up his headquarters at Riley's plantation and planned the attacks with his staff and division commanders. Many were opposed to the idea of trying to overwhelm the fort with a simple assault, but Banks wanted to end the siege as quickly as possible in order to support Grant, and felt that the 30,000 troops available to him would easily force the surrender of the 7,500 troops under Gardner, a four to one advantage. Four different assault groups were organized, under the commands of generals Godfrey Weitzel, Cuvier Grover, Christopher C. Augur, and Thomas W. Sherman (often mistakenly identified as a relative of General William Tecumseh Sherman). Banks did not choose a specific time for his intended simultaneous assault however, ordering his commanders to "...commence at the earliest hour practicable."

The effect of this was to break up the attack, with generals Weitzel and Grover attacking on the north and northeast sides of the fort at dawn, and generals Augur and Sherman attacking on the east and southeast sides at noon. The naval bombardment began the night before the attack, the 13" (330 mm) mortars firing most of the evening, and the upper and lower fleets beginning firing for an hour after 7 am. The army land batteries also fired an hour bombardment after 5:30 am. Weitzel's two divisions began the attack at 6 am on the north, advancing through the densely forested ravines bordering the valley of Little Sandy Creek. This valley led the assault into a salient formed by a fortified ridge known as the "bull pen" where the defenders slaughtered cattle, and a lunette on a ridge nicknamed "Fort Desperate" which had been hastily improvised to protect the fort's grain mill.

A Fierce Assault on Port Hudson, Newspaper illustration of the attacks on the fortifications of Port Hudson. National Archive

Soldiers of the Native Guard Regiments at Port Hudson. This squad is in the "Parade Rest" position.

At the end of this ravine between the two was a hill described as "commissary hill" with an artillery battery mounted on it. The Union troops were caught in a crossfire from these three positions, and held in place by dense vegetation and obstacles placed by rebel troops that halted their advance. The combination of rugged terrain, a crossfire from three sides, and rebel sharpshooters inflicted many casualties. The Union troops advancing west of the bull pen were made up of Fearing's brigade. These soldiers were caught between the bull pen, which had been reinforced with the 14th, 18th, and 23rd Arkansas regiments from the east side of Port Hudson, and a more western fortified ridge manned by Lieutenant Colonel M. B. Locke's Alabama troops. Once again the combination of steep sided ravines, dense vegetation, and a rebel crossfire from ridge top trenches halted the Union advance. Premature shell bursts from the supporting artillery of the 1st Maine Battery also caused Union casualties.

Seeing that his advance had been stopped, Brigadier General William Dwight ordered the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guard forward into the attack. These troops were not intended to take part in the attack due to the general prejudice against African-American troops on the part of the Union high command. Dwight was determined to break through the Confederate fortifications however, and committed them to the attack at 10 am. Since they had been deployed as pioneers, working on the pontoon bridge over Big Sandy Creek near its junction with the Mississippi, these troops were in the worst possible position for an attack of all the units in Weitzel's northern assault group.

The Guard first had to advance over the pontoon bridge, along Telegraph Road with a fortified ridge to their left manned by William B. Shelby's 39th Mississippi troops supported by a light artillery battery, the Confederate heavy artillery batteries to their front, and the Mississippi river to their immediate left. Despite the heavy crossfire from rifles, field artillery, and heavy coast guns, the Louisiana Native Guards advanced with determination and courage, led by Captain Andre Cailloux, a free black citizen of New Orleans. Giving orders in English and French, Cailloux led the Guard regiments forward until killed by artillery fire. Taking heavy losses, the attackers were forced to retreat to avoid annihilation. This fearless advance did much to dissipate the belief that black troops were unreliable under fire.

In an attempt to support Weitzel's unsuccessful assault, Brigadier Grover, commanding the northeast attack on the fortress, sent two of his regiments along the road leading northeast from Commissary Hill to assault Fort Desperate. This group had no more success than Weitzel's troops, so Grover sent three more regiments to attack the stubborn 15th Arkansas troops defending the fort. These piecemeal and sporadic efforts were also futile, and the fighting ended on the northern edge of the fortress by noon.

Thomas Sherman's afternoon attacks

Capt. Edmund C. Bainbridge's Battery A, 1st U.S. Artillery, at the siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana, 1863.

While the infantry attacks raged against the northern section of the fortress, Brigadier General Sherman lined up 30 cannon opposite the eastern side of the fortress and conducted a steady bombardment of the rebel works and battery positions, supported by sharpshooters aiming for Confederate artillery crews. This effort had some success, but General Banks, upon hearing no rifle fire from the Union center, visited Sherman's headquarters and threatened to relieve him of command unless he advanced his troops. Sherman then began the attack on the eastern edge of the Port Hudson works at about 2 pm.

These attacks included the troops of Augur as well as his own, and had less in the way of natural terrain obstacles to contend with, but in this area the Confederates had more time to construct fortifications, and had put more effort and firepower into them. One feature of the earthworks in this region was a dry moat and more abatis or cut down trees in front of the parapet. The Union attackers therefore carried axes, poles, planks, cotton bags and fascines to fill in the ditch. Another feature of the rebel defense was a battery containing two 24-pounder smoothbore (5.82-inch, 148 mm bore) as canister throwers.

In this case the canister was composed of broken chains, segments of railroad rails, and other scrap iron. Confederate Colonel William R. Miles, commanding the infantry in the sector, had also removed all the rifles from the hospital that had been left by the sick and wounded. He was thus able to equip each of his soldiers with three weapons, greatly increasing their firepower. When the Union infantry closed within 200 yards they were met by a hail of rifle and canister fire, and few made it within 70 yards of the Confederate lines. Union commanders Sherman and Dow were wounded in these attacks, and Lieutenant Colonel James O'Brien, commanding the pioneer group, was killed. At 5 pm the commander of the 159th New York raised a white flag to signal a truce to remove the wounded and dead from the field. This ended the fighting for the day. None of the Union attacks had even made it to the Confederate parapets.

The last infantry attack on the Port Hudson fortifications

Sketch map of the Port Hudson Fortifications and Grover's night attack, June 14, 1863, 3:30 pm

The successful defense of their lines brought a renewed confidence to Gardner and his garrison. They felt though a combination of well planned defensive earthworks and the skillful and deliberate reinforcement of threatened areas, the superior numbers of attackers had been repulsed. Learning from his experience, Gardner organized a more methodical system of defense. This involved dividing the fortifications into a network of defense zones, with an engineering officer in charge of strengthening the defense in each area. For the most part this involved once again charting the best cross fire for artillery positions, improving firepower concentrations, and digging protective pits to house artillery when not in use, to protect them from enemy bombardment.

Spent bullets and scrap metal were sewed into shirtsleeves to make up canister casings for the artillery, and the heavy coast guns facing the river that had center pivot mounts were cleared for firing on Union positions on the eastern side of the fortress. Three of these guns were equipped for this, and one 10-inch (250 mm)columbiad in Battery Four was so effective in this that Union troops referred to it as the "Demoralizer." Its fearful reputation spawned the myth that it was mounted on a railroad car, and could fire from any position in the fortifications. Captain L.J. Girard was placed in charge of the function of the artillery, and despite material shortages, achieved miracles in keeping the artillery functional. Rifles captured from the enemy or taken from hospitalized soldiers were stacked for use by troops in the trench lines.

Positions in front of the lines were land mined with unexploded 13-inch (330 mm)mortar shells, known as "torpedoes" at the time. Sniper positions were also prepared at high points in the trench works for sharpshooters. These methods improved the defense, but could not make up for the fact that the garrison was short of everything except gunpowder. The food shortage was a drag on morale, and resulted in a significant level of desertion to the enemy. This drain on manpower was recorded by Colonel Steedman who wrote, "Our most serious and annoying difficulty is the unreliable character of a portion of our Louisiana troops. Many have deserted to the enemy, giving him information of our real condition; yet in the same regiments we have some of our ablest officers and men." Miles Louisiana Legion was considered the greatest offender.

On the Union side, astonishment and chagrin were near universal in reaction to the decisive defeat of the infantry assaults. Banks was determined to continue the siege in view of the fact that his political as well as military career would be destroyed by a withdrawal to Baton Rouge. The resources of his entire command were called into play, and men and material poured into the Union encirclement. Nine additional regiments appeared in the lines by June 1. 89 field guns were brought into action, and naval guns from the USS Richmond were added to the siege guns bearing on the fortress. These six naval guns were 9-inch (229 mm) Dahlgren smoothbores. The guns were originally intended for a battery at the Head of Passes in the Mississippi Delta. The fact that four were finally emplaced in Battery Number 10, just east of "Fort Desperate" and two in Number 24, gives some idea of the reach and progress of the Union Navy. Each of the Dahlgren guns weighed 9020 pounds and was 9 feet long, capable of firing a 73.5 pound (33.3 kg) exploding shell.

The second assault began with a sustained shelling of the Confederate works beginning at 11:15 am on June 13, 1863, and lasting an hour. Banks then sent a message to Gardner demanding the surrender of his position. Gardner's reply was, "My duty requires me to defend this position, and therefore I decline to surrender". Banks continued the bombardment for the night, but only gave the order for what was to be a simultaneous three prong infantry attack on 1 am of June 14. The attack finally began at 3:30 am, but the lack of any agreed upon plan, and a heavy fog disordered the attack as it began. Grover's column struck the Confederate line at "Fort Desperate" before the others, and the same formidable terrain combined with the enhanced Confederate defense stopped the attacks outside the rebel works. Auger's demonstration at the center arrived after the main attack had failed, and the attack on the southern end of the line was made after daylight, and stood little chance as a result. The infantry attack had only resulted in even more dead and wounded soldiers, 1,792 casualties against 47 rebel, including division commander Brig. Gen. Halbert E. Paine. He led the main attack and fell wounded, losing a leg. After this, the actions against Port Hudson were reduced to bombardment and siege.

Six of these mortar schooners armed with the 13- inch (330 mm) seacoast mortar supported the Union attack with indirect fire from an anchorage near Prophet's Island, downriver from Port Hudson. (U.S. Army Military History Institute.)

A Confederate 10-inch (254 mm) columbiad on a center pivot mount, similar to the "Demoralizer" in Battery Four at Port Hudson

The Yankee answer: A four-gun battery of Dahlgren 9-inch (229 mm) navy smoothbores from USS Richmond set up just east of "Fort Desperate" in battery ten (see Fortifications and Batteries map) (National Archives).

A nine-inch (229 mm) Union navy Dahlgren gun set up on land for siege work as they were at battery ten at Port Hudson. The gun is whitewashed so it can be more easily worked at night. The projections at the breech are for the navy double vent percussion firing system. The crewman at the far right is wearing the Union navy uniform.

A Union sapper or combat engineer group digs a trench in the direction of an enemy fortification. A gabion provides cover from enemy fire. At Port Hudson a sugar hogshead stuffed with cotton or a cotton bale would serve the same purpose.

Last stages of the siege, June 15 to July 9, 1863

An edited version of the Port Hudson fortification map to highlight the final stages of the siege

The day after the last infantry assault, General Banks assembled some of his troops at the corps headquarters and thanked them for their previous efforts and sacrifices. He also asked for volunteers for a special attack group to be trained intensively to breach the Confederate trench line. His speech generated little enthusiasm, but a unit of 1036 men was formed and removed to a training camp in the rear to prepare for the attack. There they assembled siege ladders and organized into two battalions, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John B. Van Petten and Lieutenant Colonel A. S. Bickmore. Colonel Henry Warner Birge of the 13th Connecticut Infantry volunteered to lead the special assault regiment.

Regular siege operations were also reorganized under the command of a new chief engineer, Captain John C. Palfrey. He concentrated the efforts of the siege on three areas of the fortifications, Fort Desperate, the Priest Cap (Confederate batteries 14 & 15), and the Citadel, the southernmost bastion of the fortifications, nicknamed by Union forces as "the Devil's Elbow". These efforts did not involve infantry rushing the trenches, but a siege technique called sapping, or constructing a series of zigzag trenches, fortified batteries, and sharpshooter positions intended to isolate and suppress individual defensive bastions. The sharpshooter or sniper positions were described at the time as trench cavaliers and were raised mounds of earth, reinforced with timbers or other materials to allow riflemen to overlook the enemy trenches and fire down into them.

The Citadel was to be reduced by a powerful siege battery constructed on a hill just to the south, Union battery number 24, intended to suppress the Confederate position by superior firepower. Union batteries were also constructed on the west bank of the Mississippi opposite Port Hudson, completely surrounding it with Union artillery batteries. Union forces also made raids on opposing trenches and batteries, to enhance their own trench lines or disable enemy batteries. Some of the 6th Michigan troops opposite the Citadel were armed with the .54 caliber (14 mm) breech-loading Merrill carbine, which gave them a rapid fire edge in trench raids. On June 26, a general bombardment from Union batteries and guns of the Union fleet began, disabling or suppressing what remained of the Confederate artillery. Along with the trenching operations, the Federals also constructed three mines underneath the opposing works, two of them directed against the Priest Cap, and one under the Citadel. After the mines were finished, chambers at the end of the mines would be loaded with powder, and exploded under the Confederate works, destroying them, and blowing gaps in the trench lines. At this point an infantry assault would be launched, hopefully overrunning the entire fortification.

The Confederates responded to the siege techniques with increased efforts of their own. The grist mill at Fort Desperate had been destroyed by shelling. It was replaced by using the locomotive from the defunct railroad to power millstones, providing a steady supply of cornmeal for the garrison. Expended rifle and artillery shells were salvaged for reuse by the defense, small arms shot being recast for making new cartridges, artillery rounds reused and distributed to Confederate artillery of the same caliber, or reused as mines and grenades. Additional trench lines, obstacles, mines, and bunkers were added to the threatened bastions, making them more difficult to bombard, infiltrate, or overrun. The Priest Cap bastion had a particularly elaborate defense system, including the use of telegraph wire staked up to a height of 18 inches (460 mm), in order to trip attacking infantry. Additional field artillery and infantry were added to the defense of Fort Desperate, making sapping in that area more costly.

Various raids against Union saps were also conducted. On June 26, the Confederates launched a trench raid by the 16th Arkansas Infantry against the Priest Cap sap, taking seven prisoners, and capturing weapons and supplies. Rebel trench raiders and defenders were adept at constructing and using improvised hand grenades. Raids by Logan's cavalry were also made against Union positions outside the siege lines. On June 3 an advance by Grierson's Union cavalry against Logan's position at Clinton was repulsed. The 14th New York Cavalry was hit on June 15 near Newport, two miles from Port Hudson. Other raids struck Union foraging parties returning from Jackson, Louisiana, and captured the Union General Neal Dow, who was convalescing at Heath plantation. The biggest raid set fire to the Union supply center at Springfield Landing on July 2. These raids were annoying to Banks, but could not break the siege. On July 3, a countermine was exploded near one of the Federal mines under the Priests Cap. This collapsed the mine, but surprisingly did not cause any Union casualties. The defenders could not compensate for the constant losses of personnel resulting from starvation, disease, particularly scurvy, dysentery, and malaria, sniping, shell fragments, sunstroke and desertion. The use of mule meat and rats as rations could not maintain the health of the soldiers left standing, and was a further drain on morale.

The siege created hardships and deprivations for both the North and South, but by early July the Confederates were in much worse shape. They had exhausted practically all of their food supplies and ammunition, and fighting and disease had greatly reduced the number of men able to defend the trenches. When Maj. Gen. Gardner learned that Vicksburg had surrendered on July 4, 1863, he realized that his situation was hopeless and that nothing could be gained by continuing. The terms of surrender were negotiated, and on July 9, 1863, the Confederates laid down their weapons, ending 48 days of continuous fighting. It had been the longest siege in US military history.

Captain Thornton A. Jenkins accepted the Confederate surrender, as Admiral David Farragut was in New Orleans.

Aftermath

The surrender and that of Vicksburg gave the Union complete control of the Mississippi River and its major tributaries, severing communications and trade between the eastern and western states of the Confederacy.

Both sides had suffered heavy casualties: between 4,700 and 5,200 Union men were casualties, and an additional 4,000 fell prey to disease or sunstroke; Gardner's forces suffered around 900 casualties, from battle losses and disease. Banks granted lenient terms to the Port Hudson garrison. The enlisted men were paroled to their homes, with transport for the sick and lightly wounded. Seriously sick or wounded were placed under Union medical care. 5,935 men and civilian employees of the Confederate Army were officially paroled. 405 officers were not paroled and were sent as prisoners to Memphis and New Orleans, half eventually winding up in Johnson's Island prison camp in Ohio. Since the terms of the parole were not in agreement with parole conditions acceptable to the Union and Confederate armies then current, the Confederate Army furloughed the returned troops until September 15, 1863, then returned them to duty. This outraged some leaders of the Union army, but General Halleck, in charge of US armies, admitted the paroles were in error.

The reputation of black soldiers in Union service was enhanced by the siege. The advance of the Louisiana Guard on May 27 had gained much coverage in northern newspapers. The attack was repulsed, due to its hasty implementation, but was bravely carried out in spite of the hopeless magnitude of opposing conditions. This performance was noted by the army leadership. In a letter home, Captain Robert F. Wilkinson wrote, "One thing I am glad to say, that is that the black troops at P. Hudson fought & acted superbly. The theory of negro inefficiency is, I am very thankful at last thoroughly exploded by facts. We shall shortly have a splendid army of thousands of them." General Banks also noted their performance in his official report, stating, "The severe test to which they were subjected, and the determined manner in which they encountered the enemy, leaves upon my mind no doubt of their ultimate success." These reports had an impact far from Louisiana, or the Union army. On June 11, 1863, an editorial from the influential and widely read New York Times stated, "They were comparatively raw troops, and were yet subjected to the most awful ordeal... The men, white or black, who will not flinch from that, will flinch from nothing. It is no longer possible to doubt the bravery and steadiness of the colored race, when rightly led." These observations did much to support abolitionist efforts in the northeast to recruit free blacks for the Union armed services. By the end of the war nearly 200,000 blacks had served in the Union forces.

A significant result of the siege was the blow it gave Banks's political ambitions. If Banks had overrun the position in May, he could then have taken command of Grant's siege of Vicksburg as the ranking officer and appeared a hero. This would have redeemed his military reputation, and bolstered his political hopes for a presidential candidacy. Since Vicksburg fell before Port Hudson, Grant reaped the promotions and reputation for victory in the west, and eventually attained the White House, Banks's cherished ambition. As it was, Banks had to settle for setting up cotton deals for his northeast constituency, and arrange political alliances for a new state government aligned with Union and Republican interests in mind. He was quite experienced in this kind of scheming, and in the absence of military opportunities, economic advantages beckoned. Banks's armies had gathered million worth of livestock and supplies while engaged in operations in western Louisiana in the spring of 1863. This bounty impressed Banks, and it was also estimated that vast stores of cotton and many Union sympathizers were waiting on the Red River in eastern Texas. In response to these observations, Banks produced his one third holding plan, the idea of re-opening trade with Europe, and diverting one third of the proceeds for the Federal Treasury. This economic bonanza would once again revive his political prospects, and justify the beginning of the Red River Campaign, a military expedition into eastern Texas, the next step in military operations in Louisiana. After the war, a small number of former soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions at Port Hudson, including George Mason Lovering of the 4th Massachusetts.'

We include as much documentation with the relics as we possess. This includes copies of tags if there are identification tags or maps, as well as a signed letter of provenance with the specific recovery information.

All of the collections that we are offering for sale are guaranteed to be authentic and are either older recoveries, found before the 1960s when it was still legal to metal detect battlefields, or were recovered on private property with permission. Some land on Battlefields that are now Federally owned, or owned by the Trust, were acquired after the items were recovered. We will not sell any items that were recovered illegally, nor will we sell any items that we suspect were recovered illegally.

Thank you for viewing!